PART TWO - The Lesson

|

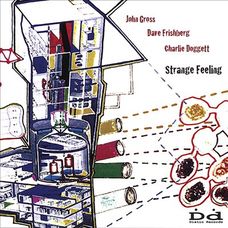

| John Gross: Origin Records photo |

LD: (I play a melody I’ve been working on)

JG: Now, when you play. Let me know if you feel any tension in your body. So play a regular C scale. Pay attention to any stress or tension you feel in you body - including your chest or face.

LD: (I play a cautious C scale). Yeah, I feel tension in my lower stomach and in my upper jaw and upper face - like I’m squinting.

JG: Okay, that has to go. Period. If you go on Youtube and look at the great players. They are very relaxed. No tension, no stress. I would observe some of the great players. They’re working hard but they are not tight or stressed out. When they play, they are completely at ease with their instrument. With most of them it’s because they’ve been playing for forty years. Or even ten years. But you have to be as relaxed as possible.

If you’re feeling stress in here (points to lower stomach) then you aren’t breathing right.

The best way to learn how to breath is free. Download it free online.

A book, you’re going to want to write this down, called The Science of Breath by Yogi Ramacharaka. It was published around 1903 or something like that. You need to learn the “Yogi Complete Breath.”

LD: That’s great! Thank you, I’ll check it out.

JG: Go through all the exercises and find ones that might help your tone production. Not that your tone is bad. Your tone is okay. You just aren’t breathing right. Because you were never taught - it’s really simple.

I was on the road with Lionel Hampton and one of his trombone players turned me on to this book. And I still have a copy and use it all the time.

LD: Great, thank you. So my air support...

JG: Air SUPPLY.

LD: My air supply?

JG: Right, supply. If you fill your lungs correctly you will already have enough support. The beauty about the saxophone is that you cannot put too much air through the instrument. It’s impossible to do. It’s physically impossible. Like the clarinet [for example] you can put too much air through and it backs up because it’s a cylinder. The sax is a cone.

Velocity might be part of your issue. But, you know, it’s a cone so you can’t ever fill it up because of the physics of the cone. There is no point where the horn won’t do more. It’s up to you. Just the breath alone will do it for you. You want to be able to play really soft and really loud and every gradation between.

JG: Let’s talk about practicing smart. What does that mean? To you, what does that mean?

LD: Maybe, being more focused or honest about what you’re practicing.

JG: You only have a limited amount of time to practice. So how much time do you practice everyday?

LD: Always at least an hour and 2 to 4 hours per day on a good week.

JG: My recommendation is 2 to 3 per day. So during that time what do you usually do?

LD: I’ll start with scales and long-tones to warm up. Then I’ll move on to any patterns or licks I’ve been working on. And if I still have some brain power left I’ll run through some Jamey Aebersold tracks. [for those that haven’t burned your brains out of Jamey Aebersold: it’s a playalong system with “minus-one” tracks designed for the use of aspiring jazz musicians]

JG: Then what?

LD: Usually by that time I’ll take a break.

JG: Now what do you do with the Aebersold stuff.

LD: I’ll pull up the chart I’m working on. I’ll work on the melody and then work on memorizing the changes. Arpeggiating the changes and root movements. Then improvise freely.

JG: Now, do you do this consistently. Or every once in a while?

LD: For sure two or three times per week.

JG: Charlie Parker practiced 3 to 8 hours per day for two years before he decided to play in public again. He never really talked about what he practiced but when he was done he sounded really good. A lot of us practiced a lot when were were in our 20s and 30s. I did even though I was a drunk. I still got better, a lot better. So then I started thinking - well what is it that I need to work on.

What do you need to work on?

What can’t you do?

Do you know?

LD: Well I can’t really do the overtones or altissimo notes.

JG: Are those important?

LD: They can be I guess. I’m more concerned with my tone. I’ve been working mostly on my tone lately.

JG: Well what do you hear? Is there a tone in your head that you’re not getting.

LD: Sometimes yeah.

JG: Then follow that. There is some really good information that Steve Lacy disseminated about playing the saxophone and about playing music. I think he has a bunch of good ideas about this. He was a great saxophone player. None of his Soprano notes were ever out of tune.

He talked about going into a practice room. He picked two note. Just two notes, a half step away, and doing nothing but playing those two notes... for 8 hours straight. After about 2 hours he said that he started to hallucinate. Now, I’ve tried to do it. I can’t even make it an hour. I thought, wow that’s really something.

LD: Not even changing octaves?

JG: No. He said that it’s amazing how much space there is between those two notes. I really need to try and do that again. You get hints of [that space] when you practice. Of course he knew every tune that Monk ever wrote. He knew all his music. Steve is extraordinary, he became one of the best saxophone players ever to play the instrument.

Pablo Casals, when he was 90, would practice a ton. Why did he still practice? He said, “Well I think I’m making progress.” Haha.

You could live 500 years and never explore all the possibilities that your brain can think of. There’s a guy Joe Maneri, his son Mike Maneri is a vibes player. Joe taught at New England Conservatory of music. He developed a system of playing quarter tone through Saxophone using different fingerings.

But let’s get to playing something. You have your Aebersold out so let’s play something.

LD: [I have Autumn Leaves on my to-learn list and the audio is ready to play so I hit play and start to play the melody. But, John interrupts me before I’m halfway through the chorus]

JG: You’re playing the melody wrong. Play the melody right

LD: [I restart the melody]

JG: That’s wrong [he stops me again]. Get the book out. If you want to know what the real changes are you need to go to the library and check out how the composer intended it to be. They have the original scores and sheet music... they probably have it online by now. But, what was it the composer intended. Okay, you have the music out now. Let’s try it again but this time play the melody right.

LD: [Off I go. And then begin to solo. A solo I’m not particularly happy with... I remember feeling a lack of enthusiasm - could have been better but it is what it is]

JG: Now, have you listened to yourself play?

LD: A little bit.

JG: I would suggest you record yourself and be ruthless. And discard everything you don’t like. Now, what are you trying to do?

LD: You mean make it through without sounding bad?

JG: Well, what is your intention? You’ve shown me you can read the notes but you have to decide how you want to play the melody. You have to decide how you want it to sound. And then when you improvise. What is your intention? You say, you’re just trying to make it through?

LD: Yeah... sometimes I feel like I don’t even know where I am in the tune.

JG: That’s because it’s a difficult art. Period. Now, I suggest that you listen to yourself and then compare the way you play the tune to other peoples versions. And see how you stack up. I mean, it’s a competition here. So you must compare yourself to the very best. Period. I mean had you come into a jam session and played I’d say “well you don’t seem quite sure what you want to do.” You’re sort of making the changes but what do you want to present to other people that you find in the tune?

If you’re just trying to make it through the changes then you’ve got a lot more work to do.

LD: So it sounds like I’m wandering?

JG: Well for one, there’s not a great swing feel going on. And there isn’t much of harmonic interest happening. There isn’t much that grabs my ear. There’s an awful lot of thinking that goes into playing. An awful lot of study. I would suggest you listen to all the alto players you can find playing over this tune and steal all the parts you like. Because that’s what we all do.

Some people say that Stravinsky first said this: “good composers barrow, great composers steal.”

If there is something that catches your ear - learn it! And analyze it and say what is it about this phrase that I like. And then, if you want to you can learn the phrase and how it fits into the chordal patterns. Then you can change it to make it your own. But, it’s all using your brain.

You copy. You assimilate it. Then you synthesize it. Clark Terry said it better. But, first you have to know what you like.

First listen to every alto player you can find. Then, listen to everyone you like and only them. If you hear some alto player play and you don’t like it. Figure out why you don’t like it. Then move on and keep looking for what you do like.

I started out listening to Charlie Parker and then gravitated toward Paul Desmond and Lee Konitz. Art Pepper’s earlier stuff was really beautiful too. His later stuff not so much because he was trying to do things he could no longer do. But, heroin and alcohol ruined his life.

I like the new guys too. Steve Coleman, and Kenny Garrett, Greg Osby and so many others that play in that style. I figured out - I was shown - where they learned that stuff from. They learned it from Bunky Green from Chicago. He played that way in the 1970’s. He developed that style of playing. He was playing the hippest shit way back then before everyone else.

LD: How do you describe that style?

JG: I don’t know how I would put it in words. You have to hear it. It’s a unique thing. All those newer guys do it. Some are a bit more intellectual and some are more emotional but it’s that style. What a tremendous influence on that generation of alto players.

I met him one time. I was playing in Chicago in 1980 with Toshiko. It was part of the Chicago Jazz Fest. Toshiko was nice because she made sure everyone had a feature and I had a feature. So I did my number. And afterwards this little black guy comes up to me as I’m getting into a cab and says “Do you know what you’re doing?” It’s Bunky! I said, “yeah I know what I’m doing.” Haha. So that was nice.

I’d like to see him again. Just to, you know, thank him for what he’s done.

Bunky was one of those guys that was largely ignored in the 1970s. Not in Chicago - he was working all the time there. But it took a while for his influence to reach places like New York.

And to know where Coltrane came from you’ll have to listen to Gene Ammons - and a bunch of other players that came before him. There are also some older recordings of John Coltrane playing alto.

Now, practicing. You have to know what you can’t do.

Someone once asked a big name player how he is able to play so well drunk. He replied, “Well I practice drunk that’s how!”

But, what’s the underlying message in what he’s saying? Everybody I have ever talked with has a different way of practicing. It works for them and that’s all you need. Find what works for you and do it. If you want to play drunk, practice drunk. If you want to play classical music, practice classical music. If you want to play Jazz, then practice Jazz!

Okay, what’s the most used scale?

LD: Maybe the dorian?

JG: No! It’s the chromatic scale. Have you mastered that scale?

LD: Well, probably not mastered it, no.

JG: Okay, what’s the second most common scale?

LD: ...not sure.

JG: It’s the pentatonic. (he plays it very quickly in a couple different keys) Sound familiar? Do you know it in all keys?

LD: No, but it sounds very familiar.

JG: Okay write out the notes. Any key just write out the scale.

LD: ( I do this... slower than he would’ve liked)

JG: Okay, now write all the chords that that scale fits in.

LD: (I struggle for an awkward 20 seconds)

JG: Okay let’s start on G (grabs my notepad I was using). What chords will fit in that scale that all chord tones are completely consonant? Okay now go to Ab. Would that scale work in the Ab chord? Now go to A.

(We continued this for several minutes)

So how many chords will this scale fit over completely consonantly?

LD: Looks like 7.

JG: Yeah! And that’s not even using any altered chords. If you add those it will fit even more! So is it a good scale to know or what?

Okay now what is the third most common scale?

LD: I have no idea.

JG: It’s the 9 note scale or double diminished or the whole/half diminished scale. Now what chords fit within this scale? We don’t have much time so here (he writes out the chords it works with).

It’s the one that is most used under the diminished chords. There are three of them and if you learn them you have something to play over all the dominant and diminished chords.

This is our vocabulary:

Chromatic

Pentatonic

9-note scale

Then you need to know where to put them in. They don’t say it like this in school. But, what you want to do is what has been done before and then develop your own. There are countless books of scales. But, what I would recommend is to develop your own.

There are other things. Practicing tunes.

A great tenor sax player, Ellery Eskelin, has a great blog. He has a very similar approach that I take to learning a tune.

I take a tune. For example I’ll take Autumn Leaves (grabs the chart from the music stand) and I’ll take each chord note by note and take it through each chord of the tune. For example, take the first chord (Cm7). Take the root (C). And see how far it will go in the tune before it becomes the wrong note. Where does it fit where does it not fit? What changes does it sound good under and what changes does it sound bad under.

Then you take the next scale degree, D, and see where it fits and where it doesn’t. So on and so forth through the entire implied scale of the first chord of the tune. Then you go to the next chord and do the same thing. Start with whole tones all the way through the tune. In time. Your body and your mind will remember this.

Then do the same thing but pick any scale degree of the first chord. Go up a direction or down a direction on each new change - but stay within a degree or two; don’t move to far from the previous note. Go through the tune until it becomes absolutely boring. Then, move to half notes. Hah! And then to quarter notes or half-note triplets and then eight notes. So on and so forth.

Do see what an intellectual game this is? You have to master the tune before you can play it. As they say, learn everything you can then forget everything and play.

So I don’t know about six months.

One thing that is key is playing with other people. Now in this day in age it’s a little harder. But, I know all over the city there are people, many many people in basements and garages trying to learn this music. It’s very important that you learn how to play with other people’s playing. How to listen and respond to each other. That’s what we did growing up and that’s what they are doing today. The idea is to find people who play as well as you do or better and play with them on a regular basis.

Music is something that needs to be played together. You could spend all this time in the practice room and come up with some unbelievably great shit. And then you go to play it out and they won’t be playing what their playing on the Aebersold records.... and it won’t work because you haven’t practiced playing with other people.

And it has to be fun.

Okay, is that enough for you?

LD: That was a lot of info for one day.

JG: And there are lots of people that practice in completely different ways and they become very good. People do things to practice that I disagree with but it works for them. So don’t have a closed mind to different approaches.

One of the sayings we have in the music business is “Don’t give up your day job”

LD: Haha, well looks like I was a little late on that advice.

JG: Hah, yeah. But, I never tell anyone that they can’t do it. Incredible progress can be made in a short period of time. What you have is a good instrument, a decent sound, a decent mouthpiece, and you’ve got some time.

So when you play you need to record yourself. Listen to yourself and compare your performance with the best performances you can find. It’s not going to be pretty. But, you have to decide on what level you want to be. What are you shooting for? If you want to be with the best you have to compare yourself with them. You don’t want to just be the best alto player in the neighborhood.

You need to listen to yourself critically. Always be critical of yourself and kind toward other people. But, hard on yourself. Because these are things that no one else will tell you.

I suggest we meet in a couple of months. And play. Not until early May.

Use your brain. Be hard on yourself. Figure out how you can best use the time that you have.

LD: Thanks John.